Perhaps it’s biggest success is it’s treatment of the kill-or-be-killed cold nature of war, which ravaged the Native American people and had a huge impact across the entirety of North America. It’s a very dark period of history and Barry doesn’t shy away from it in the least, providing a brutal portrayal of the killings and warfare mentality that swept across the vast lands.

Days Without End is far from just a war novel, though, as it takes in everything from sexuality and gender to parenthood, friendship and love along the savage road to a certain peace. Race-related themes are also touched on here and there, in particular the brutal reality of the war between the expansionist United States of America and the Native American tribes, and less so the slavery and abuse of black Americans.

Its central character, Irish immigrant Thomas McNulty, goes on to be a soldier fighting first against the Native Americans and then for Abraham Lincoln’s anti-slavery Union. However, he starts out in the home of the free as a cross-dressing entertainer, which continues to be a big part of his life, so there’s this incredible dichotomy that cuts through everything.

He’s also in love with his beau John Cole, who he meets shortly after his arrival in America following his flight from Ireland’s Great Famine. They stick together through thick and thin, whether they’re dressed as women to entertain local miners, killing Native Americans in the army, fighting the Confederacy South or trying to bring up their adopted Native American daughter Winona.

It delivers a horrifically honest portrayal of the massacre mindset behind the wars, which left countless dead and displaced huge volumes of Native American people. It daubs at the heart of morality with a many shades of grey brush that calls into account the actions of the soldiers, their order-dealing superior officers and government decision makers above them.

While it neither condemns or condones the characters it casts into life, there are no doubts about what is right and wrong. So much so in fact, that it’s tough to empathise with the central characters in the aftermath of the atrocities that they commit.

Counterbalanced against the grim reality of the wars is a beautiful poetry to the descriptions of the wilderness that Thomas travels through and the people that he comes in contact with. There’s also a no-nonsense brevity to the narration, which helps to give the story it’s cold look back on the history of the period.

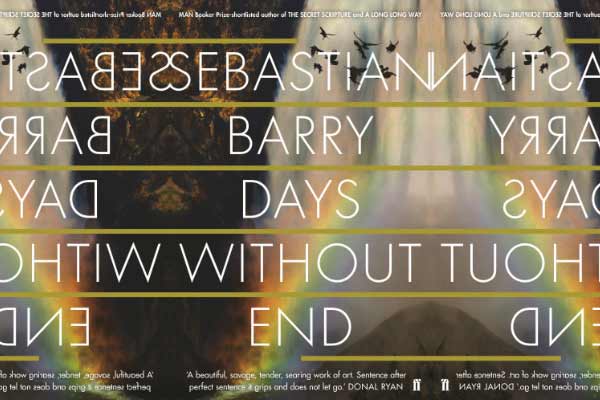

Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End comes to a close a little too conveniently, but it delivers a sweeping American epic before that, asking a lot of the reader. It’s a clever trove of subtle postulations on the themes of sexuality, gender, love, friendship, parenthood, racial persecution and war and it brings it all together with a lot of skill.

It’s easy to appreciate why it has already won the Costa Book Award and the Walter Scott Prize, and it’s clearly going to be in the running for the Booker Prize following its recent longlist nomination. It may not be quite as epic, or perfectly enclosed as either The History Of Seven Killings or The Narrow Road To The Deep North before it, but there are shades of their style and impact.

Sebastian Barry, Day’s Without End review: 4/5